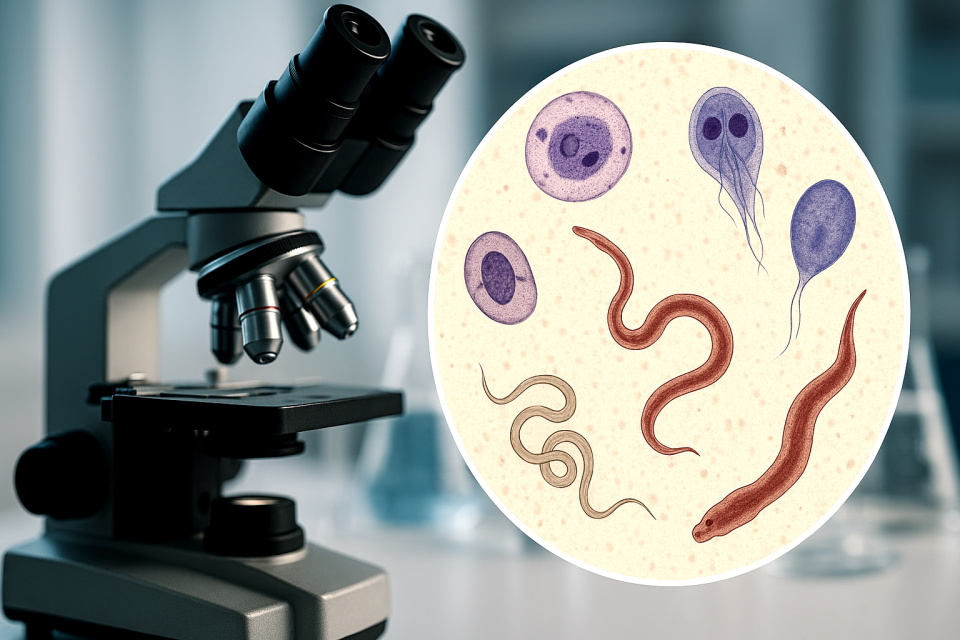

Parasites are ancient and persistent companions of humankind, so small that most people don’t realize how easily they spread, yet so adaptable that no population is entirely free from them. While modern medicine often focuses on bacteria and viruses, parasites and parasitic worms (helminths) continue to be overlooked contributors to chronic illness and recurring infections.

Among those most at risk are individuals in high-exposure professions, such as sex workers and healthcare workers, who regularly encounter diverse body fluids and environments where microscopic eggs or cysts can thrive. Unfortunately, these infections are often undetected, misdiagnosed, or dismissed altogether, leaving sufferers trapped in cycles of recurring symptoms.

Key Parasites Affecting Sex Workers

Below are the primary parasites identified in medical and parasitological literature as being of concern in sexual-contact or high-exposure contexts.

- Entamoeba histolytica (Amebiasis)

-

- Type: Protozoan

- Transmission: Fecal-oral route, especially through oral-anal sex (rimming) or contaminated hands and surfaces

- Symptoms: Diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloody stools, and in severe cases, liver abscesses

- Notes: Many carriers are asymptomatic but still shed infectious cysts that can easily pass to others

This microscopic parasite forms cysts that survive outside the body, allowing for easy transmission. Once ingested, it can invade the intestinal wall and even travel to the liver. In a sexual context, exposure through rimming or contaminated genital contact makes this a concern for both partners.

- Giardia lamblia (Giardiasis)

-

- Type: Flagellated protozoan

- Transmission: Oral-anal contact, contaminated water, or objects

- Symptoms: Greasy, foul-smelling stools, bloating, fatigue, and poor nutrient absorption

- Notes: Extremely infectious—even a handful of cysts can trigger full-blown infection

Giardia is often associated with contaminated water, but it is also spread via person-to-person contact. It attaches to the intestinal wall and interferes with absorption, leading to persistent digestive issues that are often mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome or food intolerance.

- Cryptosporidium spp.

-

- Type: Protozoan

- Transmission: Fecal-oral, especially via oral-anal sex; resistant to chlorine

- Symptoms: Watery diarrhea, nausea, weight loss, and dehydration

- Notes: Particularly dangerous for immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV-positive)

Cryptosporidium is a resilient protozoan that can survive disinfectants and chlorinated water. It is one of the leading causes of waterborne outbreaks in developed nations and has been documented spreading within sexual networks.

- Strongyloides stercoralis

-

- Type: Nematode (roundworm)

- Transmission: Skin penetration or internal autoinfection

- Symptoms: Rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or systemic infection in immunocompromised people

- Notes: Can persist in the body for decades; serious complications arise when the immune system is weakened

Unlike most worms, Strongyloides can reproduce inside the human body and re-infect the same host repeatedly without external exposure. Its larvae can burrow through the skin, often through bare feet or mucosal tissue, making it a hidden and long-term inhabitant once acquired.

- Schistosoma haematobium (Blood Fluke)

-

- Type: Trematode (fluke)

- Transmission: Contact with contaminated freshwater in endemic regions

- Symptoms: Blood in urine, pelvic pain, bladder damage, and increased HIV susceptibility

- Notes: Female Genital Schistosomiasis (FGS) can mimic sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

This blood fluke enters through skin exposed to infected water and settles in blood vessels near the bladder or genital tract. In women, it can cause genital lesions that resemble other STIs, often leading to misdiagnosis. It’s been linked to higher HIV transmission rates in endemic areas.

- Trichomonas vaginalis

-

- Type: Protozoan

- Transmission: Vaginal, oral, or anal sex

- Symptoms: Vaginal or urethral discharge, itching, or burning

- Notes: Often coexists with other STIs and increases risk of HIV transmission

This is one of the few parasites universally recognized as a sexually transmitted infection. Trichomonas irritates the mucosal lining, creating small tears that make the exchange of bloodborne pathogens more likely. While treatable, it often recurs if both partners are not treated simultaneously.

Amplifying Effects of Helminths

Helminths (parasitic worms) do not merely take nutrients—they alter immune function. When these worms invade tissue, the immune system releases specialized white blood cells known as eosinophils. These cells attack parasites by releasing enzymes meant to destroy them, but they can also harm surrounding tissue.

Over time, this process can cause necrosis, scarring, and chronic inflammation in genital and intestinal tissues. This damage increases vulnerability to other infections, particularly viral STIs such as genital herpes or HIV, which exploit broken or inflamed tissue to establish infection.

Why This Matters for Sex Worker Health

- Higher Exposure Risk

Sex workers face elevated exposure through high-frequency intimate contact and practices involving multiple body fluids, including oral-anal or unprotected anal sex. These practices make it easier for enteric (intestinal) parasites to find new hosts.

- Underdiagnosis and Misdiagnosis

Doctors in industrialized countries often dismiss the possibility of parasitic infections, assuming they occur only in developing nations. Many patients who present with recurring gastrointestinal distress, fatigue, or genital irritation are instead treated symptomatically—with antibiotics or antifungals that offer temporary relief but do not eliminate the root cause.

- Immune System Compromise

For individuals living with HIV or other immune-compromising conditions, parasitic infections can escalate from mild to life-threatening. Protozoans like Cryptosporidium and worms like Strongyloides can cause systemic infections that require immediate medical intervention.

- Lack of Public Health Awareness

Because these conditions are not routinely screened for in sexual health clinics, they often go unnoticed. Many infections remain chronic, silently weakening the host and perpetuating transmission cycles within communities.

A Broader Perspective

Less than one percent of all parasite species have been formally identified. Each known species may have hundreds of undocumented genetic variations, meaning that the true diversity, and threat, of parasites remains vastly underestimated.

In natural medicine and holistic health circles, practitioners like Wayne Rowland have long suggested that addressing parasitic load can profoundly improve health and vitality. His experience treating high-exposure clients, including sex workers and healthcare providers, underscores that modern society’s sanitized image does not guarantee protection from the microscopic world that surrounds us.

Raising awareness about parasitic threats is not about fear, it’s about empowerment. By understanding how these organisms spread and survive, individuals can take practical steps toward prevention, testing, and treatment.

Key steps include:

- Practicing rigorous hygiene before and after intimacy

- Washing hands and body thoroughly after contact with potentially contaminated fluids

- Considering periodic natural or prescribed parasite cleansing protocols under expert supervision

- Seeking second opinions if persistent digestive or genital symptoms remain unexplained

Parasites are part of the human story, but they need not define our health. When we move beyond denial and address them with knowledge, compassion, and scientific curiosity, we begin to reclaim control over the unseen world within, and around, us.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Parasites – Sexually Transmitted Infections.” CDC.gov, 2023.

- World Health Organization (WHO). “Intestinal Parasites and Sexual Transmission.” WHO Parasitology Department Reports, 2022.

- Stark, D., et al. “Sexually transmitted intestinal parasites: A review of transmission, diagnosis, and management.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Schistosomiasis – Female Genital Schistosomiasis.” CDC.gov, 2023.

- Okeke, T. C., et al. “Female genital schistosomiasis and HIV infection: A review.” Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 2014.

- Smith, H. V., and Nichols, R. A. “Cryptosporidium: Transmission, pathogenesis, and diagnosis.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2010.

- Olsen, A., et al. “Helminths and immune modulation: Consequences and opportunities.” Trends in Parasitology, 2012.

- Rowland, Wayne. The Disease Symptom Elimination Program and Silver Water Protocols, private field research, 2010–2014.

- Rowland, W. and Masters, D. M. “Parasitic exposure and chronic illness among high-risk populations.” St. Paul’s Free University Archives, 2012.

- World Health Organization. “Strongyloides stercoralis: Global distribution and risk factors.” WHO Neglected Tropical Diseases Database, 2021.